School Mascot-Offending or Honoring?

This article won The Frederick News Post‘s first place “Mike Powell Excellence in Journalism Award” for a column on a state or national subject.

This 50th school year marks a time to remember our past, celebrate traditions, and plan the future for Linganore. Does planning for the future mean that the school should re-visit its use of a Native American mascot?

The school mascot is a symbol of pride and heritage; however students do not always realize what it means and how it relates to the Native American culture.

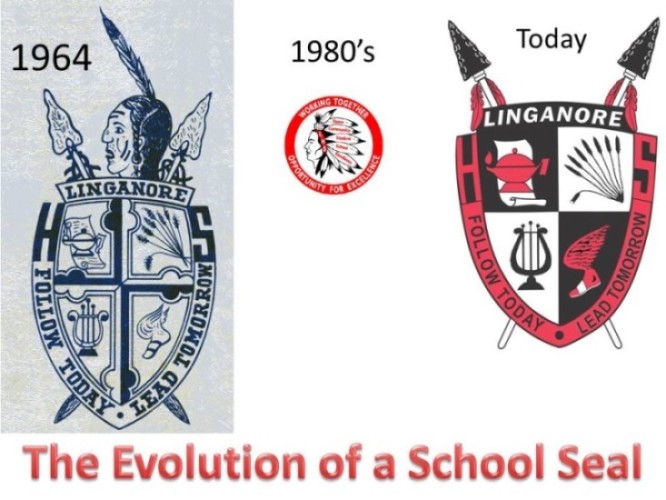

The seal was designed in 1963 by student Carlton King. He wanted to pay tribute to the school’s Native American heritage, while highlighting the school’s academic philosophy.

The school’s first students voted for the Indian mascot, so Mr. King used a Native American warrior and two lances as the focus of the shield. Other symbols were added to capture Linganore’s educational philosophy: a scroll of knowledge and a lamp of light were included in the top left hand corner to represent academics; a lyre was added to represent the arts; shafts of wheat were added to represent the understanding and appreciation of agriculture; Mercury’s foot was added to represent teamwork and spirit of competition in sports; and a cross separated the four quadrants to signify spirituality.

As our society has become more aware of diversity, using Native Americans as mascots and symbols is widely debated around the country and can be the cause of sensitivity.

According to a CBS news report, the Oregon State Board of Education voted in May 2012 to ban all Native American mascots, nicknames, and logos.

Washington state schools have also considered removing the mascots.

The Redskins have been situated in Loudoun County, Virginia for several years; but recently there has been talk about them moving back to Washington D.C. The District’s mayor Vincent Gray recently told The Washington Post that if they do, he would like to see the name changed.

The Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian on The Mall in Washington, D.C., sponsored a convention in early February 2013 about racist stereotypes in sports, and The Redskins were featured.

Various other schools, universities, and sports teams have been either challenged or forced to remove their mascots.

According to Robin Shield, public affairs specialist at the Office of Public Affairs for Indian Affairs at the Department of the Interior, using Native Americans mascots and can easily offend.

“…It’s always a risk when you put people to be the subject of ridicule … the fans of one team are always going to go after the fans of the other team… and that’s what happens with sports,” she says.

“…to… a non-native, it’s a symbol, a mascot. To a native person, it’s a way of life,” says Elayne Silversmith, librarian for the Smithsonian Institution, and member of the Navajo Nation. “And native people are the single ethnic group that is used as a mascot …Why not any other group? Why not, say, Jewish people, or African Americans, or Haitians? And it’s only Native Americans.”

Some people in the Linganore community might remember a case in 2002 which was brought against the Frederick County Public School system concerning Linganore High School’s use of the Native American mascot. Mr. Richard Regan, then a member of the Maryland Governor’s Commission on Indian Affairs, filed a complaint as an individual against the school, saying that Linganore using the mascot “makes a mockery of American Indian people;” “destroys the self-esteem of American Indian school children;” and “promotes racial stereotypes.”

However, much of the community did not agree with Regan’s actions at the time.

In a letter to The Frederick News-Post from 2002, Barbara Kyle, of Mount Airy, wrote, “If you have attended any high school sports you will see that the school’s symbol/mascots are not degraded but held up as a source of pride for the participants.”

This same thinking is shared by many current students.

“It’s a mascot,” says sophomore Julia Peigh. “It’s something that the school is proud of. It’s something that’s demonstrated as fierce, and it’s honestly something that’s good for our football team!”

But according to Mr. Regan, simply having the mascot representing the school is racist and could even be construed to violate Maryland’s diversity regulation.

“It’s a violation of the Maryland regulation of diversity inclusion,” he says, “which states that all schools in the State of Maryland have to create academic and learning settings where people’s differences are recognized, embraced, and valued. And you can’t tell me that an American Indian student going into that school is going to be able to reach his or her full potential when they have to look at that mascot every day.”

However, according to current principal Dave Kehne, no Native American student has ever complained about this. “Certainly, if any student felt that he or she would be victimized in any way, including a victimization of one’s race, we would certainly explore the issue;” he said.

“I do not believe that any concerns were ever brought to us by the Board of Education,” said Mr. Harold C. Mosser, former principal, in response to Mr. Regan’s 2002 complaint. “We just thought that we treated everything with great respect. It was something that we were proud of, and that’s why we went ahead and maintained the Native American image.”

Marge Lyburn, principal until 2009, says, “I think our students were sensitive to the fact that they didn’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings, but I had no students who suggested to me that we we were hurting someone’s feelings.”

Three to four years ago, Mr. Kehne took the opportunity to review the meaning of the Native American mascot with students. “The students initiated wearing the headdresses, and I used that point as a way of bringing the students in, and asking them, ‘What does it mean, for you and your peers, when you wear that? Why do you wear that?’ and the conversation kept going on. Some of the kids, who had just been wearing it for fun, quickly realized… that they needed to be even better than the average citizen when [they] wore that.”

“I think nearly all of our students would think it’s not okay to offend people based on their racial background, but that they would hope the intention would be made clear;” says Mr. Kehne. “…I don’t think our students would consider the image of the Native American to be intentionally derogatory.”

And students do not.

“…it’s not racist;” says Juia Peigh. “…In essence, we’re really highlighting Native American people. We’re putting them in the spotlight.”

“It honors the school,” says junior Jeffrey Smith.

When the old Linganore High School was demolished in 2008, the Alumni Association petitioned to bring back the original version of the school’s shield, as designed in 1963 by Carlton King.

The shield had only been in use officially at Linganore for perhaps 10 years. It was only recently “re-discovered,” and Linganore decided that they would use this shield as their primary logo because it more accurately represented Linganore academically, and it included other symbols that represented Linganore well; as opposed to another logo that had been in use at the school at the time which depicted an image of a Native American with a headdress which had the words “Home,” “Community,” “Student”, “School,” and “Excellence” written in it.

However, the current version of the shield is not the original, because it does not include the Native American and cross.

With the demolition of the old school, the Alumni Association saw opportunity to highlight Linganore’s history and heritage by returning the use of the old shield, complete and with the Native American and cross.

They requested that the shield be placed in various locations around the school and campus, including on the press box in the stadium, on Main Street, and in the school’s dining hall.

Mr. Kehne responded to this request by saying that he agreed with the Alumni Association because he did want to honor the past. “…but at the same time,” Mr. Kehne said, “not unlike any other organization… as society changes, sometimes images do, too.”

Both the Alumni Association and the administration agree on the need to honor the past. There is a showcase under the east stairwell, which the Alumni Association maintains, that frequently displays LHS heritage items, like last year’s fall display of FFA (Future Farmers of America) items from the past.

Currently, there is a wood carving of a Native American Lancer inside, created by Joe Stebbling of Thurmont. The 1,000 lb. white oak Native American serves as a dignified reminder of our strong school heritage.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Linganore High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase camera/recording equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs. We hope to raise enough money to re-start a monthly printed issue of our paper.