Life in Topaz Japanese Internment Camp: Mary Murakami inspires with survival story

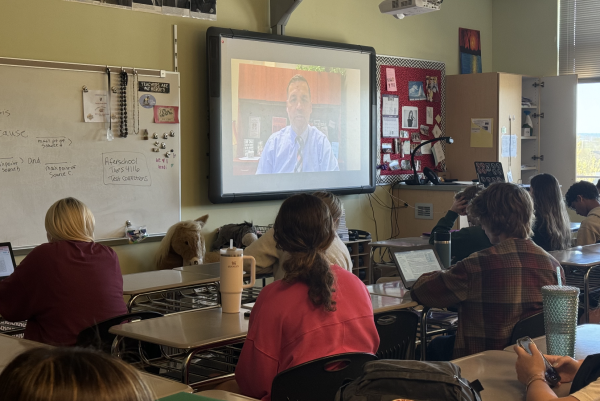

Junior Gerald Fattah talks to Mary Murakami after her session.

May 1, 2019

For most teenagers, age 14 is a time spent adjusting to the trials and newness of high school. Mary Murakami, a Japanese-American in the 1940’s, had a different experience. At just 14 years old, she and her family were transported to Topaz Internment Camp in Utah.

For history students, the Japanese internment camp experience became startlingly real in the form of Mary Murakami, a petite, gray-haired 92 year-old who came to speak in April.

Several hundred students were mesmerized by her story.

She described how following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, fear of anything affiliated with Japan set in to Americans. By February of 1942, the government had passed Executive Order 9066, taking away the freedom and civil rights of anyone with even 1/16th Japanese blood. Over 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry were relocated to internment camps throughout the western United States.

“They came to our homes and told us we could take with us what we could carry. We sold our furniture and left our valuables behind. Our new life was packed in a suitcase,” said Murakami. They came to our homes and told us we could take with us what we could carry. We sold our furniture and left our valuables behind. Our new life was packed in a suitcase — Mary Murakami

Murakami’s family was stripped of their freedom and their identities, reduced to identification numbers. In Murakami’s case, hers was E22146. Her family of seven was stuffed in a whitewashed horse stall with only a few straw stuffed cots until the permanent camps were ready.

“There was a little library with books organized alphabetically that had been donated. My sister and I decided to start with ‘A’ and see how far we could get before the permanent camps were ready. By the time we got to ‘C’, we were being put on trains headed for Topaz,” she said.

Murakami’s home for the next three years was 55CD, a small space with only seven cots and a pot belly stove. Instead of the bustling city she had grown up in, her new surroundings were watchtowers and barbed wire fences.

The living conditions were the bare minimum. There were communal bathrooms in the center of each block and a mess hall where the whole camp would eat. The bathrooms were wide open and offered no privacy for the internees.

“We not only lost our freedoms, but our privacy as well,” said Murakami.

One of Murakami’s sharpest memories is that of the food served at the camp. The meals were made by their fellow internees and was the complete opposite of the diet they were accustomed to, traditional Japanese dishes. Dissatisfied with the American farm food, many stopped eating. To combat this, camps passed rules forcing the internees to get food. When they responded by throwing the unwanted food away, the garbage cans were guarded. Their final solution was peanut butter, apple butter, and jelly sandwiches (the ingredients for these were on every table as second helpings of food were not allowed).

Murakami said, “We ate so many of those sandwiches: to this day I will not allow apple butter in my house.”

In 1943, the government issued a loyalty questionnaire to the internment camps. Questions 27 and 28 sparked frustrations within the camps. Question number 27 asked if the men and women would be willing to serve in the United States military on combat duty. This question caused concern, as men feared that their willingness to serve would be considered synonymous with volunteering.

Question number 28 asked if they would pledge full allegiance to the United States and revoke any allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. This question caused unrest as well. For some, they were angered at the fact they were being asked to revoke allegiance to the Emperor that they never held. For others, cutting ties to Japan would mean getting rid of their only citizenship, as new immigrants were barred from obtaining U.S. citizenship due to racial discrimination. Those who refused to answer or said no to questions 27 or 28 were sent to Tule Lake, a segregated prison camp.

“It always bothered me, those questions. Our loyalty was being tested, but if we were not loyal, we would have refused the camps and put up a fight. We did not riot. We just made the best of the situation we were in. For some reason, that wasn’t enough for the government,” said Murakami.

By 1944, the draft had begun in the camps. Murakami’s oldest brother was drafted and sent to fight in the war.

“What sticks out to me still to this day is the fact that they didn’t let my parents outside the fences to say goodbye. The image of my parents on one side of the fence and my brother on the other side is still sharp in my mind.”

Murakami’s husband and many others volunteered to serve to prove their loyalty and formed the MIS and the 442nd unit – two of the most decorated units in the military even today. After the war, they were all given Congressional gold medals for their service.

Despite everything the internees lost, they still had friendship that stood the test of time. After Murakami was released from Topaz, she and her camp friends had reunions annually to keep their connection alive. The last reunion was their 72nd reunion.

“The one thing that got us through was friendship. You had nothing else, but you had friendship and people that were going through the same thing you were. We were not alone.”

Social studies teacher Mr. Beaver organized the event and said, “I thought Mary Murakami would be the perfect speaker for students this year. I heard her speak ten years ago and it was one of those speeches that I can still remember. I asked her to come because this event is often skipped over a lot in history classes, and it’s relatable to students because she experienced it in high school.”

Junior Payton Smith attended the event and said, “I was so touched by her story, and I thought it was really heartwarming when she talked about how important friendship was. It was super inspiring.”

Murakami’s story gives a voice to thousands who were silenced amidst the distraction of World War II hysteria. Her firsthand account of what she experienced teaches our generation about a subject that does not get talked about enough and helps us to appreciate what we may take for granted.

Carol Wolfe • Jan 25, 2021 at 7:16 pm

I am looking for relatives of Mr. Zio Murakami who was held in Topaz Camp in the 1940’s. At that time he was a gardener in Woodside CA, and a good friend of my father’s. The family he worked for held his possessions for him until his return. He lived from 1901 to 1985.