Entertainment media, including movies, television shows and videogames, give a unique glimpse into the world. They do this not only through their own content, but also through the direly complex conditions in which they are often enveloped.

Earlier this year, creative industries around the world banded together to fight against these ever-worsening conditions. While the groups spent weeks attempting to come to an agreement with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), a group representing many major studios and streaming services, they were unable to do so, and the situation quickly escalated.

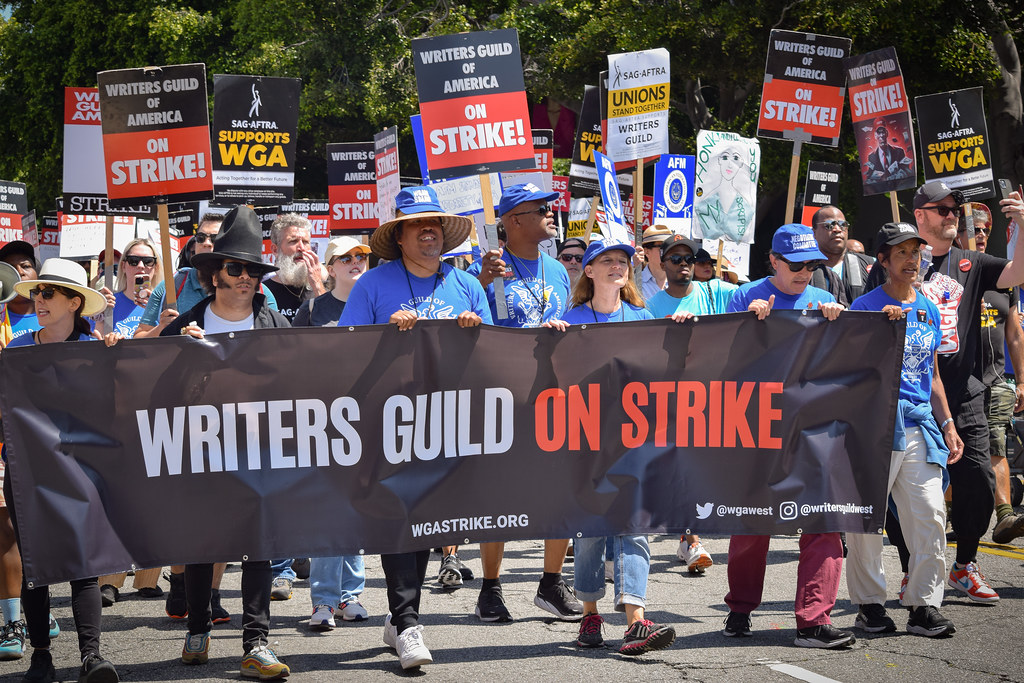

The series of strikes began with the 2023 Writers Guild of America (WGA) strike, which began on May 2, but quickly expanded to include the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) on July 13.

In just over a month, a peaceful war had been waged against Hollywood’s corporate captors and turned the entire industry on its head, leaving consumers to mourn the delayed release of their favorite movies and shows.

That is not to say that the WGA and SAG-AFTRA were in the wrong; their strikes were started with a number of concerning issues in mind, such as unfair wages, minimum staffing requirements and the exponential rise in the use of AI-powered tools and content.

“I know it started with a lot of regular union type of issues: pay, royalty payments, etc. It did involve AI… because the studios always seek to save money, and if you have an AI-generated script (you will save a lot),” said Linganore English teacher and accomplished screenwriter Damon Norko.

The last of these was by far the most important. In just the past two years, the advent of systems like ChatGPT and Midjourney have made incredible leaps in the artificial intelligence world, allowing both literary and visual artists to create beautiful works by typing nothing more than a few lines into a computer.

Although incredible, these unimaginable improvements immediately brought concerns to the skilled creatives who already worked in the fields these AI tools seek to aid. Novelists, screenwriters, graphic designers, animators and actors all felt as if their job securities were threatened by these new creations. They were certain the studios would use them if left unchecked.

“[R]aw material will be generated by AI, in terms of formatting and scenes and so on” Norko said. “And then, they [the studios] would just pay some writer to give it a more professional feel. In other words, [they would be] short circuiting the whole writer’s process.”

AI would be able to give studios the ability to create art and plots that would take a professional hundreds of hours, or even recreate an actor’s face entirely without their permission.

Due to the gravity of this legitimate concern, the WGA and SAG-AFTRA felt as if their hands were forced by the AMPTP’s unwillingness to cooperate. Both organizations demanded security for their roles in the industry: actors wanted to ensure that use of their likeness is consensual and properly compensated, and writers want to ensure that their creative rights are not infringed upon.

The second most prominent of the issues being addressed is pay. Of course, money makes the world go ‘round and Hollywood is no different. Over the years, they have adapted a series of unfair tactics to put down staff’s monetary rights.

The most problematic of these issues is called the “mini room,” a tactic which involves a studio using a much smaller number of writers, who might even be paid an unfairly low amount, to conserve a series’ budget.

A typical writers room may consist of seven more writers, while these mini rooms can sometimes consist of as little as two individuals. This one tactic damages the industry in a number of ways. It destroys the job market for writers, leads to individual writers being far overworked and results in underdeveloped projects being aired for audiences.

Consequently, another one of the WGA’s demands was a minimum staffing requirement on writer’s rooms. This includes six writers, with at least four on board prior to a series being greenlit.

Norko believes the tactic “would result in no more writers ever, because how are you ever going to develop writers when nobody ever gets paid except for the big people. Then they die off and it would destroy the entire community of Hollywood writing.”

For the SAG-AFTRA, the biggest pay concern came from the uprising of streaming platforms and the total lack of residual payments for series and movies put on those platforms. This is a peticular issue that the AMPTP has seemed entirely unwilling to change, likely because it may cause them such a large amount of money.

For the entirety of May through September, the WGA, SAG-AFTRA and AMPTP continued an unending cycle of negotiations that saw unwillingness for compromise from both sides.

On September 20, it was announced that the groups had begun negotiations yet again. Over the course of the next two weeks, the WGA and AMPTP were able to come to a deal which satisfied both parties, and the WGA strike officially ended on October 9 with 99% of WGA members voting in favor of the new deal.

“It seems like they’ve resolved it, [but] I don’t think it’s going to last,” Norko said. “I think give it ten years, and there’s going to be another huge problem.”

SAG-AFTRA has yet to come to a deal with the AMPTP and negotiations are ongoing.

Until all parties involved have reached a fair agreement that allows everyone to be treated how they deserve, the battle continues.