Immune to Violence: I’m not surprised when I get alerts about school shootings

Violence (noun): Behavior involving physical force intended to hurt, damage, or kill someone or something.

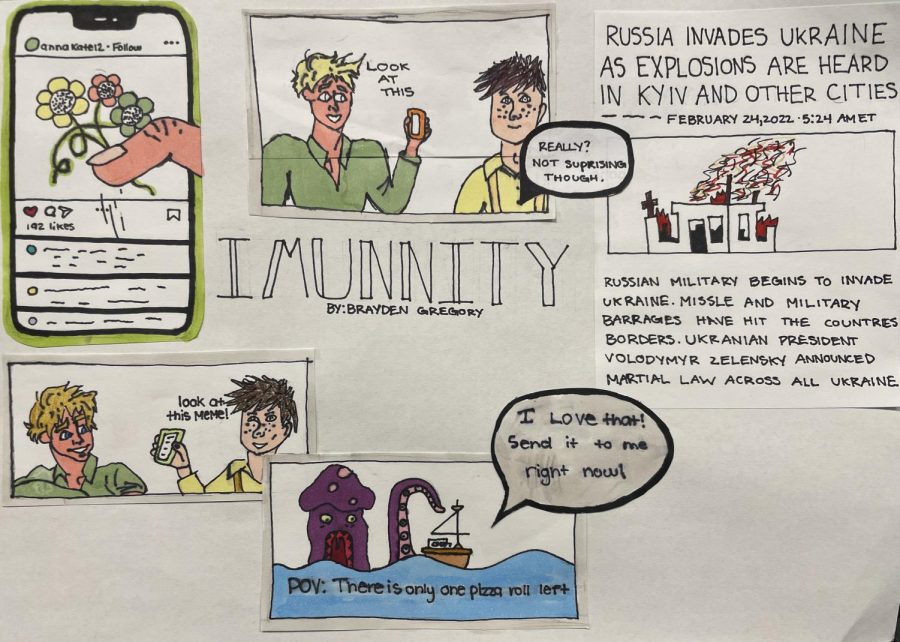

Cartoon to show how millions of teenagers and children are exposed to constant bombardment of violence, negativity, intolerance, and hatred in one form or another on the major news networks, and especially on social media platforms.

It has become a normal activity for teenagers to scroll through endless pages of hashtags and reposts of brutality, murder, and overwhelming gory violence, desensitized to hatred, intolerance, and violence on social media platforms.

Last week I got an alert on my phone saying there was a school shooting in a Las Vegas high school. My first thought was a lack of concern. “Wow, another school shooting.”

Why is that my first reaction to hearing horrific news?

Reminiscing about my childhood, of course, there were acts of violence, abductions, murders, and global conflicts. But they did not seem to consume every waking hour of our daily lives.

My mom would let me play outside alone, without having to worry about my safety. For the most part, life seemed to be more relaxed, less stressful, and less complicated, but perhaps I’ve just become more aware of my surroundings.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, an association of pediatricians with the mission to ensure the health of children, funded an experiment about the effects of violence in media.

Exposure to violence in media, including television, movies, music, and video games, represents a significant risk to the health of children and adolescents. Extensive research evidence indicates that media violence can contribute to aggressive behavior, desensitization to violence, nightmares, and fear of being harmed.

Welcome to a normal teenage world.

The research repeatedly proves that the younger generations are affected by violence in the media. Are you surprised that this experiment was published in 2009?

Thirteen years later, if anything, we know much more about the harm of exposure to unlimited violence.

In Volume 116, Part 2 of Child Abuse & Neglect (2021), recent data were collected to measure the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have led to an upsurge in children’s experience of violence in the home and online.

In the experiment, the researchers monitored conversations on Twitter to measure increases in abusive or hateful content and cyberbullying.

The result of the violence-related posts was among the topics with the highest growth after the COVID-19 outbreak. The analysis of Twitter data showed a significant increase in abusive content during the isolated restrictions.

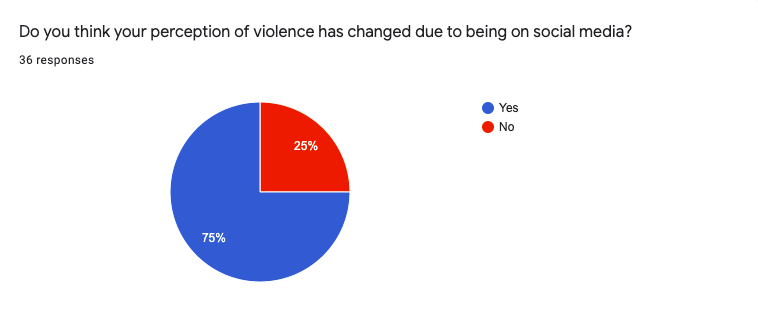

Lancer Media conducted a survey where high school students were asked about their reaction to seeing insensitive posts on social media. Typical responses included:

“I’m used to it.”

“It’s everywhere. Why would I be shocked?”

“At this point it’s normal.”

“In today’s world, violence is at every corner. There’s no way around it. No matter how small, it’s bound to happen. You constantly have to mentally prepare yourself for that because, if not, you’ll constantly walk on eggshells, and in this world that’s just not possible,” said one student.

The Surgeon General’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Television and Social Behavior was formed to assess the impact of violence on the attitudes, values, and behavior of viewers. The resulting report and a follow-up report by the National Institute of Mental Health identified these major effects of seeing violence on television:

- Children may become less sensitive to the pain and suffering of others.

- Children may be more fearful of the world around them.

- Children may be more likely to behave in aggressive or harmful ways toward others.

Exposure to media violence can desensitize people to violence in the real world that, for some people, watching violence in the media becomes enjoyable and does not result in the anxious arousal that would be expected from seeing such imagery.

But, the damage is already done.

Airline stewardesses tend to be a “popular” target for assault and anger. Vyvianna Quinonez violated FAA regulations by not wearing her mask properly, when asked by a flight attendant to comply with the masking and seatbelt policy, Quinonez pushed the flight attendant. The flight attendant later required treatment with a bruised, swollen eye, as well as a cut that required three stitches, as well as three chipped teeth.

A waitress at a South Jersey diner was abducted and beaten up by a group of customers after she confronted them when they tried to leave without paying for their $70 meal.

A few weeks back, the administration at LHS asked all student drivers to attend a meeting to address the issue of students continuously coming late to school. The reaction from the students was far from respectful. Students began yelling and refusing to listen or give their opinion respectfully.

Every day at lunch, my table jokes asking when the next physical fight will be. Last week someone threw food across the lunchroom aiming to hit someone. Bystanders watched and laughed.

How can we protect ourselves and future generations from seeing such horrific things online? How can we reverse the trend and become more caring, more aware of others’ suffering, and work for change?

It’s a fine line, when do you know if you’ve crossed the threshold? Government censorship goes against the First Amendment but would it be so bad if less violence was presented and normalized on television, video games, books, and online pages?

Within the last two years, minors and adults put their focus on the rising death toll count due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, this led to many becoming unfazed by the common occurrence.

“Because of how much violence is posted on social media, you begin to not get surprised after a while,” said an anonymous surveyor.

If the experience of seeing people dying, in real life or the media, becomes normalized, you may no longer experience an emotional reaction to it. You may not cry; you may not feel sad or angry. You may continue with your day as if nothing ever happened.

“There’s a lot of violence in the world that people report, but violence is unavoidable so I’m somewhat numb to it,” said one student’s response.

When I checked my phone in early February, there were currently 1.1 million posts on Instagram under #violence and under #death, there is 11.4 million.

“Honestly, I would think there would be more, but you have to account for some fact pages and news pages and stuff who use that but then there are other accounts, personal ones who use that tag and sometimes can be more graphic than others and it’s horrible. It feels disheartening to know and see it because out of all those posts there’s not one thing you can do to help any of them,” said one student response.

Social media platforms require you to agree to certain conditions when downloading the app. Twitter states the following in regards to posting violence.

You may not threaten violence against an individual or a group of people. We also prohibit the glorification of violence. Learn more about our violent threat and glorification of violence policies.

Instagram states this:

It’s never OK to encourage violence or attack anyone based on their race, ethnicity, national origin, sex, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religious affiliation, disabilities, or diseases. When hate speech is being shared to challenge it or to raise awareness, we may allow it. Graphic violence is not allowed and we may remove videos or images of intense or graphic violence.

Yet I constantly see violent posts on both platforms.

An account on Instagram under the username of @violence has 411k followers and is updated daily showing images and videos of violence. It has a backup account listed in the bio, in the case of being deactivated.

It’s hard to fathom that this account exists, along with countless others with similar content.

What went wrong in this world? People find enjoyment in watching “funny” videos on YouTube and other platforms where people end up getting hurt. It’s inhumane.

But I’m a hypocrite. I’ve watched the same videos in my room.

I find it interesting that, the current generations, are less likely to be affected by violence; however, they tend to be the more scared of it. If we break it down, it makes sense, for my generation to be more cautious and aware of what could happen at any point in time.

According to Jean Twenge, a psychology professor at San Diego State University and the author of Generation Me and iGen. In an Atlantic article called “Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?” she argues smartphones have radically altered the nature of social interactions and consequently mental health.

During their childhoods, they experienced the rise of the helicopter parent and anti-bullying campaigns, with a culture so focused on keeping children safe, many teens seem incredulous that extreme forms of violence against kids can happen at any moment.

Millennials and Gen Z are far more conscious of mental health issues and more able to articulate them than their parents were, said Sarah Flower, manager of health promotion for the U of A’s Human Resource Services.

“This generation is much more in tune with what they need. People will say, ‘I have anxiety,’ or, ‘I’ve been diagnosed with depression-they are very open to sharing that,” said U of A sociologist Lisa Strohschein.

Summer Unplugged is an annual summer campaign to get everyone in the USA off their phones and outside for their summer break. The campaign focuess on families and produce a challenge sheet with hints and tips to get parents and children all supporting each other to set boundaries around their vacation phone use.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Linganore High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase camera/recording equipment and software. We hope to raise enough money to re-start a monthly printed issue of our paper.